Edge Collective

34. The real risks of Long COVID

A review of recent research on the rates and impacts of Long COVID.Key takeaways:

- Even mild COVID infections can lead to long-term, sometimes permanent effects ("long COVID"), including brain fog and debilitating fatigue.

- Rates of long COVID -- in both children and adults, and after both mild and severe infections -- are estimated at between 10 and 20%.

- The risk of developing long COVID symptoms seems to increase with each subsequent infection.

- Long COVID can impact all organ systems in the body; even mild infection seems to increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, and dementia, and can result in what appears to be permanent cognitive impairment and physical disability.

- There is as yet no known cure for long COVID.

Suggested readings:

"Long COVID is harming too many kids" -- Blake Murdoch, Scientific American 11/18/2024.

"Long COVID in children and adolescents" -- Lopez-Leon et al, Nature Scientific Reports 6/23/2022

"Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms, and recommendations" -- Davis, Topol et al, Nature Reviews Microbiology 1/13/2023

"NIH-funded study finds long COVID affects adolescents differently than younger children" -- NIH.gov, 8/21/2024

"Long Covid can impair quality of life more than advanced cancers" -- R. Hall, The Guardian, 6/7/2023

Clip from Tasmanian inquiry into Long COVID and children: "Is it responsible to allow the reinfection of children with a novel coronavirus that causes long-term sequelae, brain damage, increases in childhood iabetes & kidney issues along with a whole range of other compounding sequelae?”

Clip from testimony at UK Long COVID investigation: "Long COVID is a new childhood disease whose prevalence is equivalent to childhood diabetes."

"Clinical data indicate that COVID-19 causes cardiovascular complications, regardless of the severity of the disease" -- Kubiasak et al, Nature Scientific Reports 11/30/2024

Interview with Dr Ziyad Al-Aly about Long Covid (3/15/24) See 15 min mark: 20 million americans with Long COVID; very few recover. No treatment; no cure; spontaneous recovery is very rare; at 20 minute mark, multiple body systems, every new infection increases risk of long covid.

TEDx Santa Barbara Interview with Dr. David Putrino on Long COVID

COVID is significantly more lethal for kids than the flu (Bloomberg)

Higher viral load is associated with worse long-term COVID outcomes (Tromp et al, Nature Scientific Reports Dec 2024)

1 in 4 healthy young Marines report long-term physical, cognitive or psychiatric effects after mild COVID -- (Porter et al, The Lancet, Nov 2024)

"COVID can raise the risk of heart problems for years" -- NYT, Nov 2024

"People with hypermobility may be more prone to long Covid, study suggests" -- Guardian article covering a study published in BMJ, March 2024.

Jan 2024 Congressional hearing on Long COVID. Good introduction by Bernie Sanders; testimony by Dr. Al-Aly is here

December 2024 Interview with Dr. Arijit Chakravarty regarding COVID safety

March 10 2025 -- Long-term impacts of COVID on body, NYTIMES

Higher rates and greater impact of long COVID than previously thought

Most people now seem to believe that COVID-19 has become a 'mild' disease, and that -- aside from precautionary vaccination against the odd chance of a more severe case -- it is no longer worth taking many (or any) precautions against infection.

Indeed, while some people still do feel 'knocked out' for a few weeks after infection, most COVID-19 cases now seem to be 'mild', especially for those with up-to-date vaccinations.

There is, however, a growing body of research indicating that, in many people, even a mild COVID-19 infection can lead to longer-term symptoms lasting months or even years -- a condition referred to as 'Post-acute sequelae (PASC) of COVID-19' or 'long COVID'.

Estimates vary, but there seems to be consensus that at least 7% and perhaps as many as 25% (1 in 4) of COVID-19 cases result in long-term symptoms, including brain fog, severe fatigue, and an increased risk of Type I diabetes. For some, these longer-term symptoms resolve within a few weeks, or months; for others, they have not yet resolved.

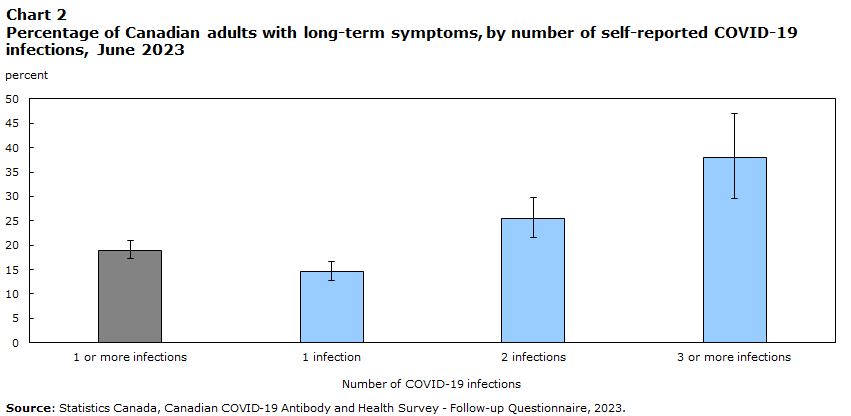

Further: there is now evidence that the risk of developing 'long covid' symptoms increases with every infection, whether the infection was initially mild or severe. By the third infection, the chances of developing long-covid symptoms is estimated to be over 35%, or greater than 1-in-3 (see 'Chart 2' below).

) ) |

|---|

| Chart 2 from Kuang et al, "Experiences of Canadians with long-term symptoms following COVID-19", Statistics Canada 12/8/2023. |

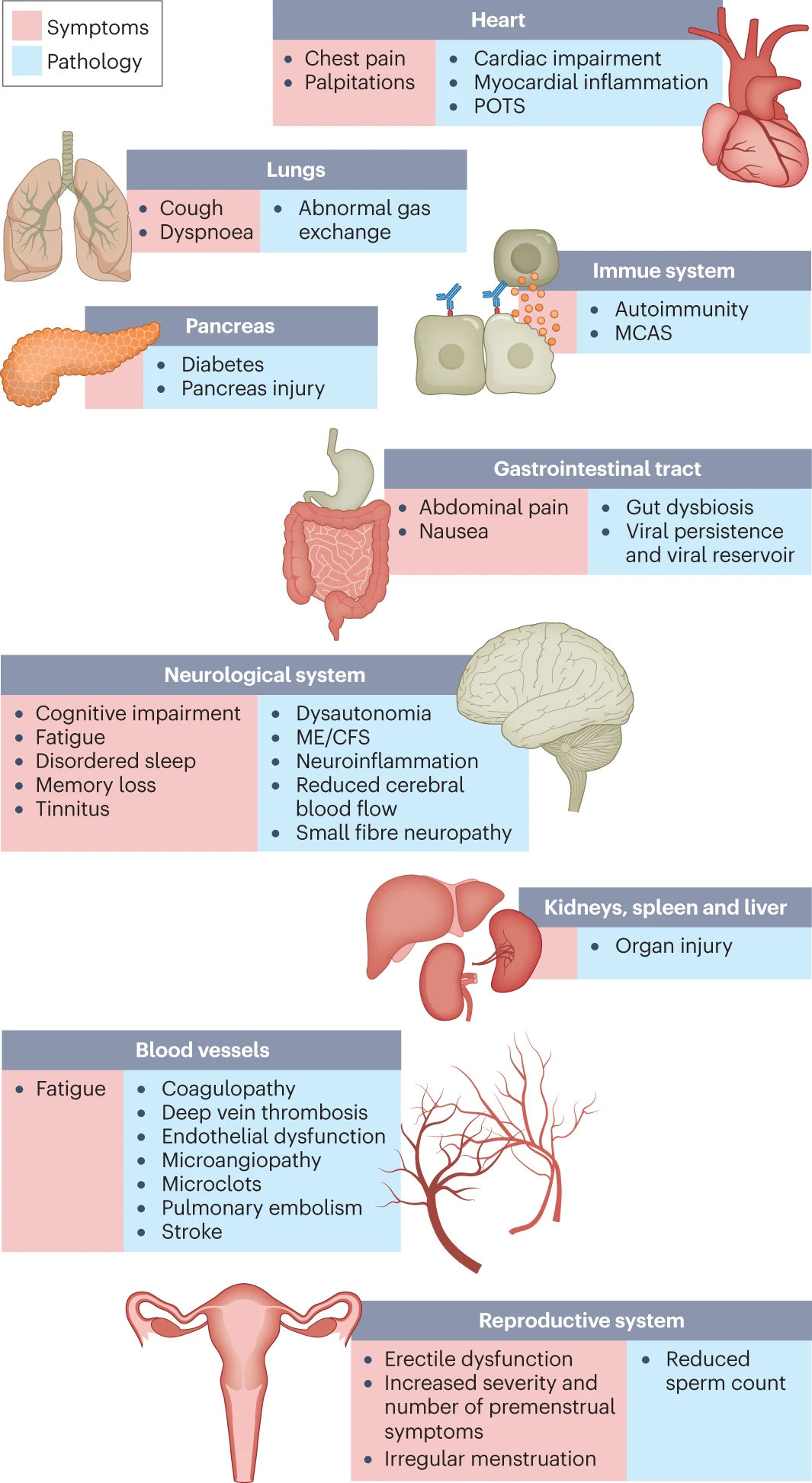

It is now understood that COVID-19 can impact every organ system in the body, including the heart and the brain. Even mild COVID-19 infection is now known to significantly increase the chances of severe heart disease, stroke, and dementia.

New understanding of mechanism of long COVID

In fact, researchers no longer characterize COVID-19 as a 'respiratory-only' disease, but as 'vascular' disease. Increases in microscopic blood clots after infection with COVID-19 had already been widely observed, and recent evidence points to a likely mechanism: fibrinogen, a key component of blood clots, was shown in a 2024 Nature paper to bind to the COVID-19 spike protein; researchers believe that this feature of the virus -- enabling it to induce clotting throughout the body -- could account for most of the symptoms of long COVID. (An explanatory interview with the authors of the Nature paper is here).

Key papers:

- "Fibrin drives thromboinflammation and neuropathology in COVID-19", Ryu et al., Nature, 8/28/2024

- "Discovery of How Blood Clots Harm Brain and Body in COVID-19 Points to New Therapy", K. Quiqly, Gladstone Institute, 8/28/2024

- "Clotting proteins linked to long COVID's brain fog", C Offord, Science, 8/31/2023

) ) |

|---|

| Figure 1 from Davis, Topol et al, "Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations", Nature Reviews Microbiology 1/13/2023 |

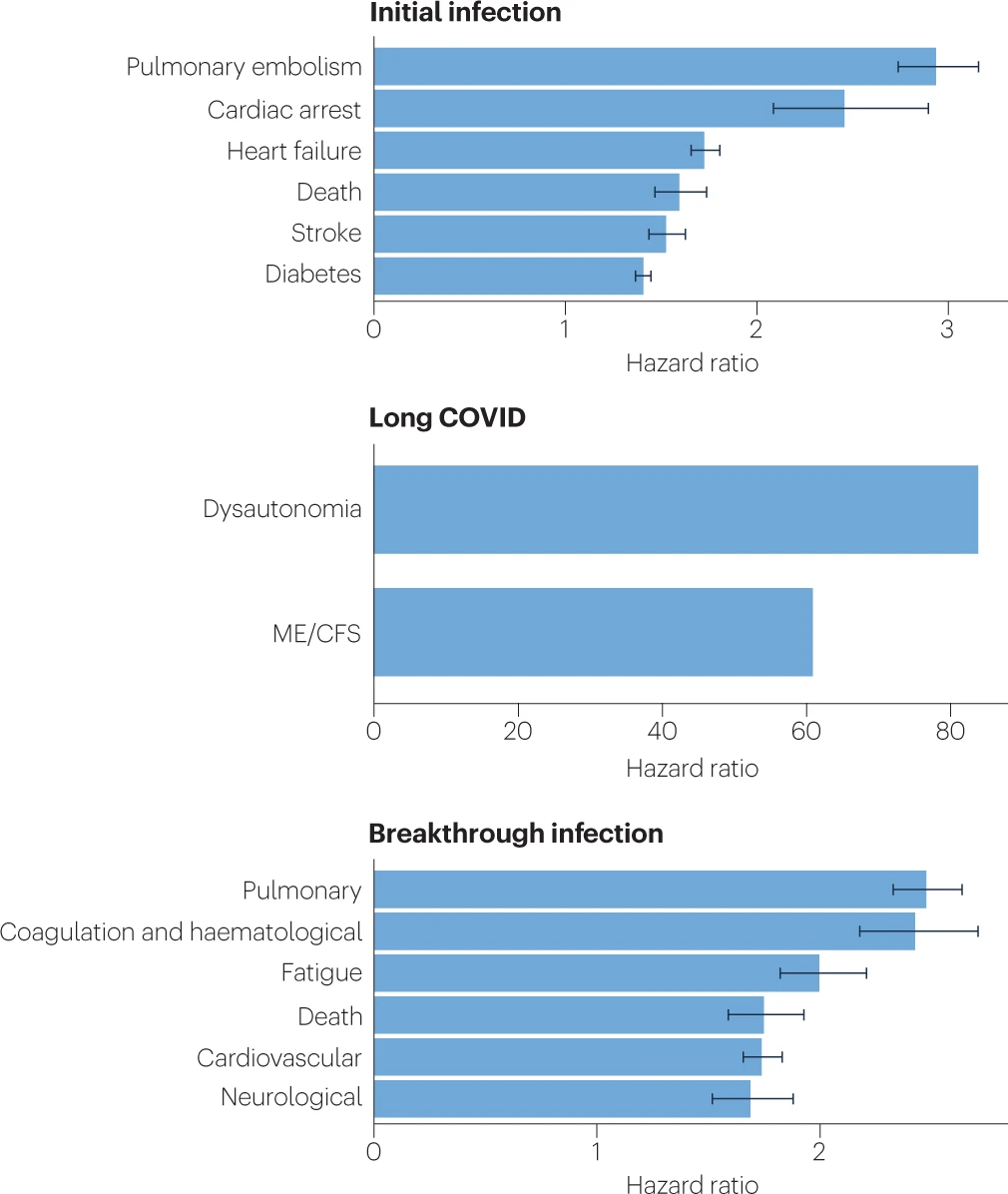

) ) |

|---|

| Figure 2 from Davis, Topol et al, "Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations", Nature Reviews Microbiology 1/13/2023. 'Hazard ratios' represent the relative risk for a person with a COVID infection relative to someone not infected. For comparison, smoking 10 to 20 cigarettes a day leads hazard ratios of 1.61 for stroke, 1.5 to 2.5 for cardiac arrest, 1.3 to 1.5 for diabetes, 1.2 to 1.5 for pulmonary embolism, and 1.8 for death. |

There are currently no well-established effective treatments or cures for long covid; for some, it appears to be a life-long condition, and can be debilitating.

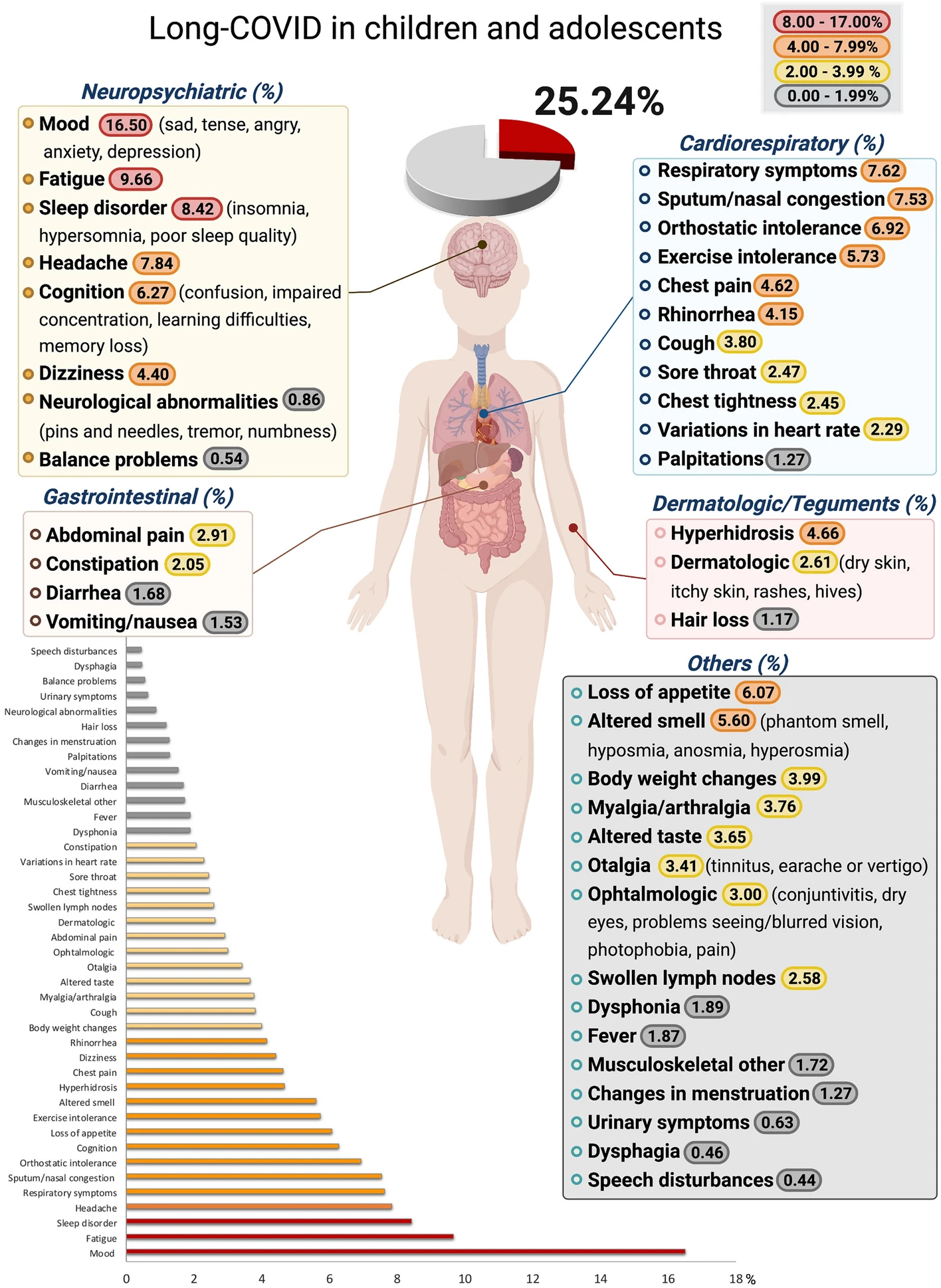

Impact of Long COVID on children

The latest estimates suggest that between 10 to 20 percent of children infected with COVID go on to experience long-term symptoms, including:

- trouble with memory or focusing;

- back, neck, stomach or head pain;

- daytime tiredness and low energy.

A recent JAMA study (Gross et al, "Characterizing Long COVID in Children and Adolescents", JAMA, 8/21/2024) noted that long COVID symptoms in children "affected almost every organ system".

|

|---|

| Figure 2 from Lopez-Leon et al, "Long-COVID in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analyses", Nature Scientific Reports 6/23/2042 |

Studies indicate that COVID infections can result in long-term damage to

- cardiovascular ("Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19", Xie et al, Nature Medicine, 2/7/2022;

- neurological "Long-term neurologic outcomes of COVID-19", Xu et al, Nature Medicine 8/22/2022; and

- immunological systems "The immunology of long COVID", Altmann et al, Nature Reviews Immunology, 7/11/2023

as well as increasing the relative risk of new onset pediatric diabetes (see "SARS-CoV-2 Infection and New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Among Pediatric Patients, 2020 to 2022", Miller et al, 10/14/2024)-- even in children with mild or asymptomatic infections.

Why are more people not taking precautions?

Despite the relatively high risk of this potentially debilitating condition, few seem to be taking precautions against infection.

One reason may be that long covid research does not currently seem to be a significant part of mainstream discourse; few seem to be aware of the results of recent studies.

Another reason may be the delay between initial (often mild) infection and the later emergence long-covid condition, which makes it difficult for most people to make the connection between their ongoing symptoms and COVID-19.

| “Not all people even know that their condition might be caused or exacerbated by COVID,” Estiri said. “So those who go and get a diagnosis represent a small proportion of the population.” |

|---|

| from "Long COVID may be far more common than previously known", Boston Globe, 11/16/24" |

Yet another reason that few people seem to try to avoid infection currently is that the risks of longer-term COVID-19 impacts seems generally to have been minimized.

Understandably, the initial focus in the COVID-19 pandemic was on preventing or reducing severe illness or death due to the virus; and initially, no long-term data was yet available. But even some of the longer-term research into COVID's impacts has ended up providing a false sense of security around long COVID.

For example: a study in a prominent medical journal reported in 2023 that the rate of long COVID symptoms in children was 'strikingly low', at approximately 0.4 percent, a result that was widely publicized. Subsequently, this study was retracted due to methodological errors; more recent studies now estimate the rate of long COVID in children to be between 10 and 20 percent. (See "Long COVID is harming too many kids", Blake Murdoch, Scientific American 11/18/2024.)

Weighing the costs of risk reduction

A final reason that so little attention currently seems to be paid to long covid risks is that for many, the actions required to significantly reduce the risk of infection are either impossible, or would incur too great a financial or social burden.

Masking when in shared indoor spaces can often be highly incovenient, or socially charged. Eating in restaurants poses a high infection risk, but is a cherished activtiy that many would refuse to give up.

Even the use of indoor air purifiers is often now seen as being 'overkill' for a disease that most believe no longer poses significant risks.

What can be done?

If people fully understood the risks of long COVID and were to take them seriously, there are relatively low-cost measures that might significantly reduce infection risk, including:

- creating more opportunities and developing infrastructure for outdoor gatherings;

- widespread use of indoor air purifiers;

- masking when in shared public spaces with strangers;

More signifcant and costly changes might include the development of forms of life that allow for social and work interactions to occur within a relatively 'protected' pod of people, which then interacts with the rest of the world in either high-ventilation settings (e.g. outdoors) or while masked. Such forms of life are not so unusual, historically: many rural and even suburban communities allow for this sort of protective 'isolation' to be maintained.

There is also, of course, the hope that an inexpensive and widely-avaiable vaccine that prevents infection might become available. It is hard to predict when or whether such a vaccine would become available.