Edge Collective

UMass Amherst -- Ventilation & Filtration

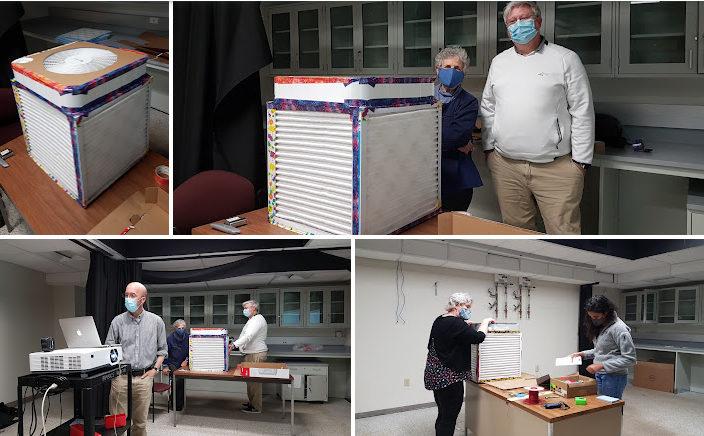

UMass Amherst Physics STEM Seminar Nov 2, 2021-- building Corsi-Rosenthal boxes and learning about DIY ventilation assessment andUMass Amherst Physics STEM Seminar

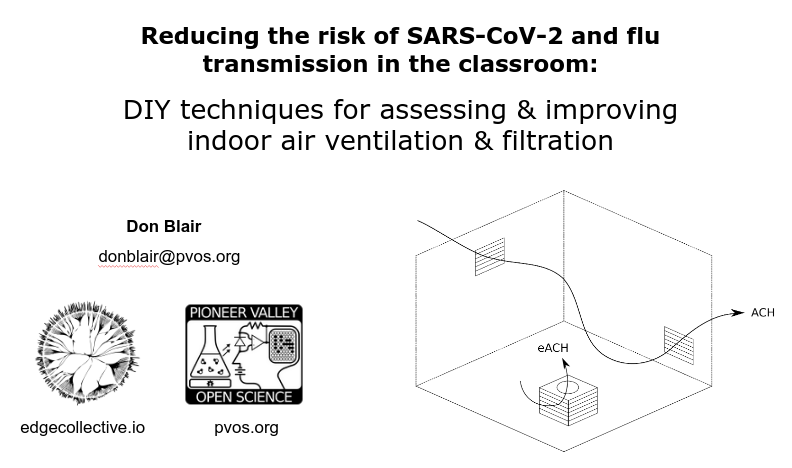

Title: Reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 and flu transmission in the classroom: DIY techniques for assessing and improving indoor air ventilation and filtration

Date: Nov 2, 2021

Abstract. In the last few years, improving indoor air quality has become a major global public health concern. In this seminar we’ll present both 1) a simple method for assessing a classroom’s indoor ventilation rate using CO2 monitors, with reference to recently published recommendations for mitigating SARS-CoV-2 transmission; and 2) a low-cost, easy-to-build DIY air purifier design that can remove virus-laden particles from indoor air spaces at a significant rate. We’ll finish the seminar with a ‘live build session’ in which we’ll demonstrate the construction of a DIY air purifier, and use a hand-held anemometer in order to estimate its potential impact on indoor air quality for classrooms of various sizes. Throughout the seminar, connections to STEM pedagogy will be suggested and solicited.

Corsi-Rosenthal Build Event at UMass

Video Presentation

Recorded presentation:

Slide Deck (PDF)

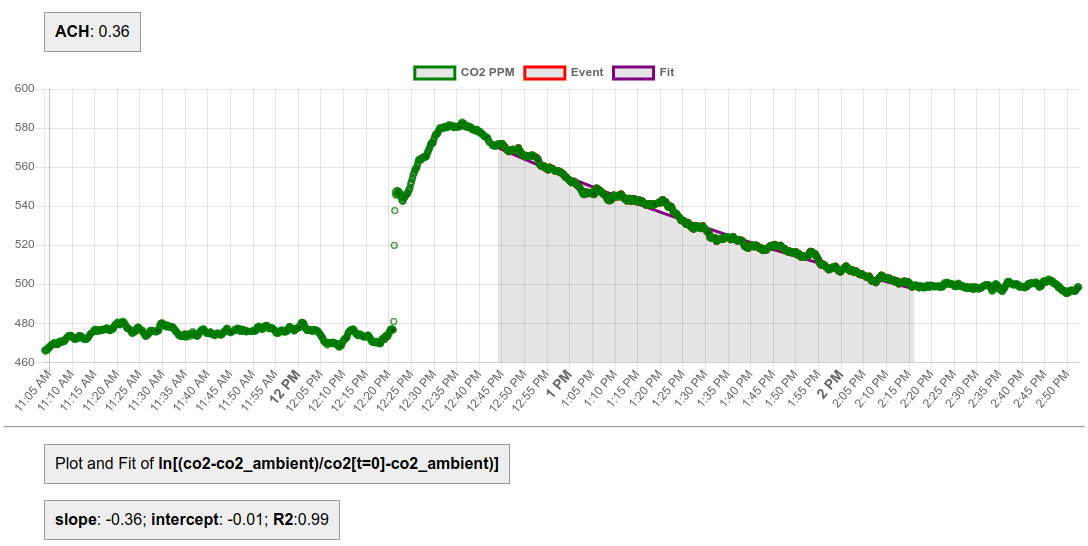

ACH analysis of CO2 decay after event

Notes / Supporting Material

COVID is airborne. The intuition should be: cigarette smoke, avoiding second-hand smoke.

Complications: We don’t know if there’s a smoker in the room, and we can’t smell it. But you now have an intuition -- if you were worried about secondhand smoke, you’d know that someone on the other side of the room can still be a problem if all the windows and doors are closed and the ventilation is poor. You’d also know that it can still be an issue if a smoker was recently in the room. The other complication is that folks are wearing masks. This helps significantly. But it’s not foolproof -- [show graphic]. Most folks are wearing cloth or surgical masks. So, what are the other knobs we can turn to reduce risk? Ventilation and filtration. That’s what we’ll focus on here.

First: very few known cases of COVID transmission outdoors. So, the biggest knob to turn, if we can, is to be outdoors. If possible, at least do meals (when you’re unmasked) outdoors.

But if you have to be outdoors, then we want to make the ventilation as safe as possible. Of course, there are limitations -- we might be heating the air, and maybe we can’t afford to open all the windows and doors and maintain a certain temp (aside: long underwear!) (STEM: energy calculations here)

So, what conditions indoors should we aim for? How can we know how far away we are from them?

Let me introduce a concept here: ‘air changes per hour’. Think of it as the number of times per hour that there’s a room’s worth of flow into the room.

There are converging lines of evidence that 6 ACH or more is a good target for indoors. Without going into it -- hospital patient rooms; HSPH recommendation. Studies of rates of ventilation indoors and infections that occurred in various parts of hospitals. Also: 10 L / s / person has been a standard for a while. Recently, there’s modeling that indicates that when people maintain > 2m distance indoors, 10 L / s / person inhalation risk isn’t very different from outdoors; and for a typical size classroom (180 m**3) of 30 people, 10 L / s / person is indeed 6 ACH. So, for now, let’s just take 6 ACH as a good target (but really, as much as you can afford to do!). HSPH also suggests that much lower than 5 ACH isn’t good.

(wells-riley)

Now, with ACH in mind, another core concept is that airborne contaminants are cleared as an exponential process. Derivation -- final equation.

Now, if you’re trying to assess indoor ventilation rates, you can use a balometer. But another nice trick is to use a ‘tracer gas’ method. In essence, you introduce a contaminant, and then measure its concentration over time. What you then get is an exponential decay down to whatever steady state you expect (in our case, atmospheric). (show Dinsmore initial experiment). You can fit an exponential to this; if the time axis is in hours, you can then consider the rate to be an estimate for ACH.

Caveats: HVAC zones. Nearby empty classrooms or full classrooms. Then the mass balance derivation is more complicated. Need to look into this to see how much it would impact the estimate.

Folks are using CO2 monitors in classrooms already. (Aside: instantaneous PPM useful when very low (< 800 ppm, ventilation probably good enough) or very high (above 1500 ppm, not good); but intermediate is hard to interpret.) Very commonly used one: aranet4. Phone bluetooth app. [demo of github.io aranet4 code -- show that open source. STEM: code this. Add some explanatory material; should be able to change the assumed steady state CO2 ppm]

But we can do better. Open hardware. (pvos.org) Easy to assemble. Board design avail online. In Belfast, they’ve used one of these systems in an engineering class, where they’ve been working on Arduino programming [show Belfast decays, including with windows]. Circuitpython. Credentials just edit-on-the-board as a USB drive (UF2 system). Also: bayou.pvos.org is easy to set up (demo).

General idea: a lending library for CO2 monitors -- they can be given out, with remote instruction. This has sort of been tested in Belfast and in Hasbrouck.

Now I’d say: useful to assess ventilation in order to try to understand it. Perturbing system can give great insights. Learn about measurement error. Flows, mass balance. But in the end the reality is a) not always easy to interpret at first, and b) not always possible to change (can’t open windows or doors).

So: filtration -- passing air through filters that can remove virus. When you know CADR, you can then estimate equivalent ACH, or eACH. Folks already have one or two installed in a classroom. Issue: not all of them have specs that can be trusted; often they’re not within budget. Reason for DIY: you know the ingredients. You can test them. Can get more performance per $ (see review).

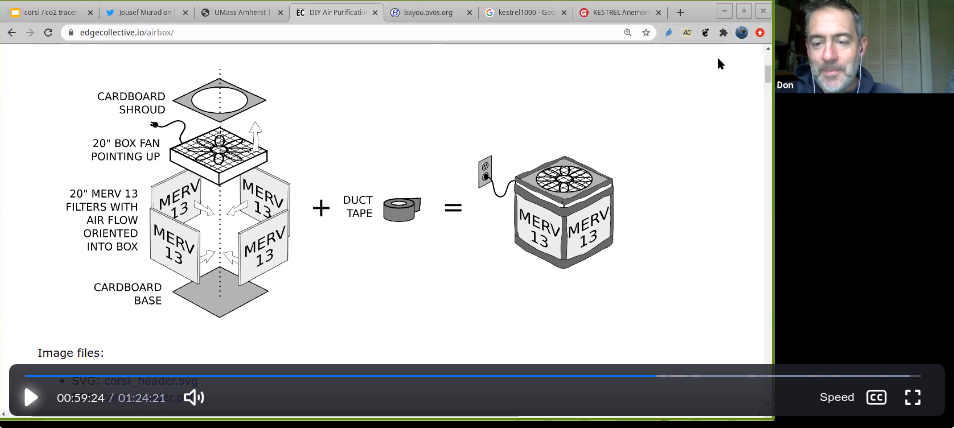

Basic initial idea was: put a filter in front of a fan. It works. But Corsi-Rosenthal came up with a better version: a box of filters. Better because: more surface area, less strain on fan motor, greater flow. Review of basic design. Key points: filters are directional; make sure you’ve got a seal. Point upwards. Fan shroud (reverse air flow phenomenon at corners). Measure cadr (and test reverse air flow). Can then use this to estimate eACH. Then you can figure out how many to put in classroom.

STEM ideas: visualizing and measuring air flows. Building and improving electronics. Same system can be used in several other contexts -- flooding, farming, outdoor navigation, etc (show edgecollective ideas).